When you have a large codebase, chains of dependencies can become very deep. Even simple binaries can often depend on tens of thousands of build targets. At this scale, it’s simply impossible to complete a build in a reasonable amount of time on a single machine: no build system can get around the fundamental laws of physics imposed on a machine’s hardware. The only way to make this work is with a build system that supports distributed builds wherein the units of work being done by the system are spread across an arbitrary and scalable number of machines. Assuming we’ve broken the system’s work into small enough units (more on this later), this would allow us to complete any build of any size as quickly as we’re willing to pay for. This scalability is the holy grail we’ve been working toward by defining an artifact-based build system.

Remote caching

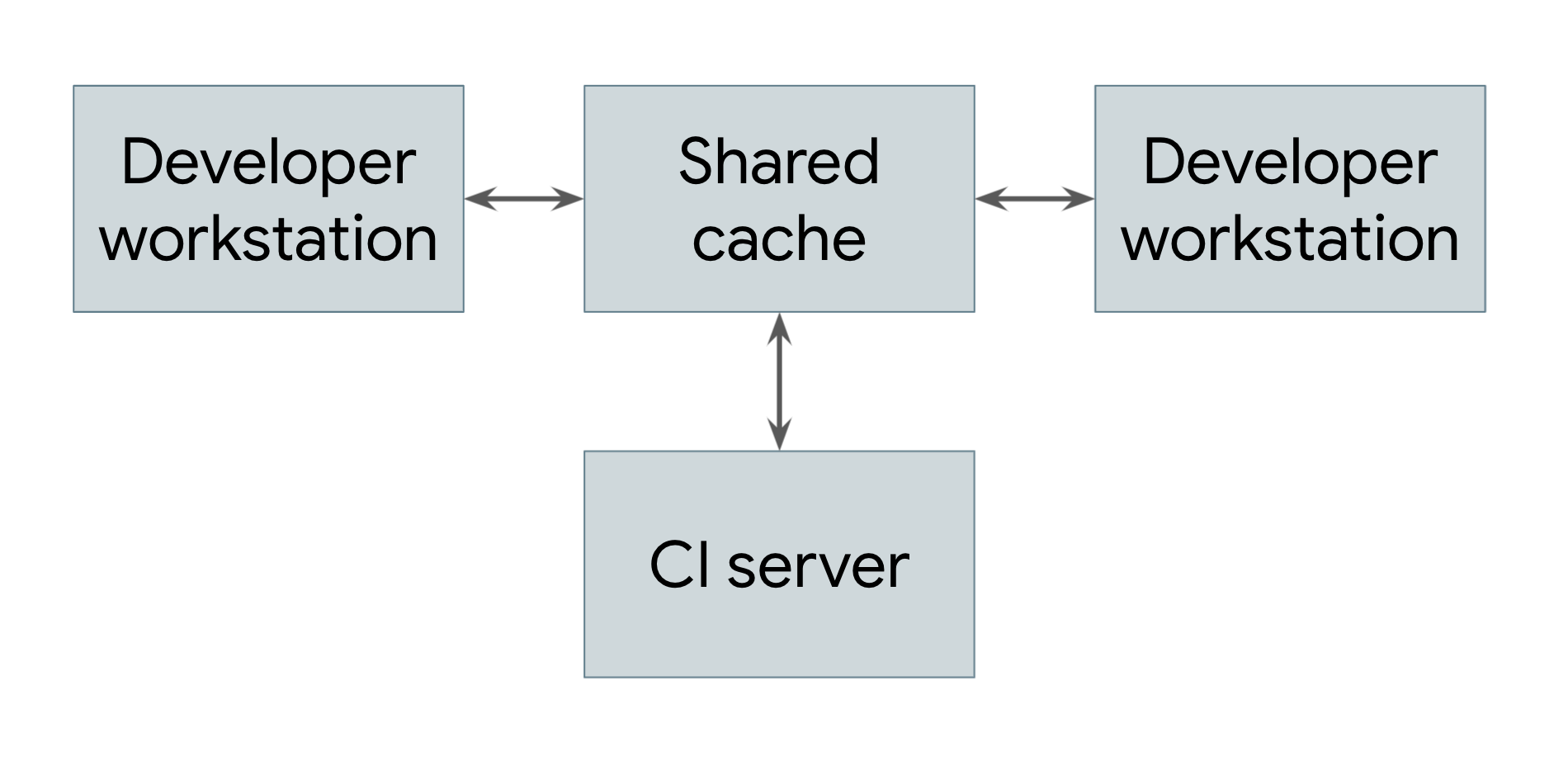

The simplest type of distributed build is one that only leverages remote caching, which is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A distributed build showing remote caching

Every system that performs builds, including both developer workstations and continuous integration systems, shares a reference to a common remote cache service. This service might be a fast and local short-term storage system like Redis or a cloud service like Google Cloud Storage. Whenever a user needs to build an artifact, whether directly or as a dependency, the system first checks with the remote cache to see if that artifact already exists there. If so, it can download the artifact instead of building it. If not, the system builds the artifact itself and uploads the result back to the cache. This means that low-level dependencies that don’t change very often can be built once and shared across users rather than having to be rebuilt by each user. At Google, many artifacts are served from a cache rather than built from scratch, vastly reducing the cost of running our build system.

For a remote caching system to work, the build system must guarantee that builds are completely reproducible. That is, for any build target, it must be possible to determine the set of inputs to that target such that the same set of inputs will produce exactly the same output on any machine. This is the only way to ensure that the results of downloading an artifact are the same as the results of building it oneself. Note that this requires that each artifact in the cache be keyed on both its target and a hash of its inputs—that way, different engineers could make different modifications to the same target at the same time, and the remote cache would store all of the resulting artifacts and serve them appropriately without conflict.

Of course, for there to be any benefit from a remote cache, downloading an artifact needs to be faster than building it. This is not always the case, especially if the cache server is far from the machine doing the build. Google’s network and build system is carefully tuned to be able to quickly share build results.

Remote execution

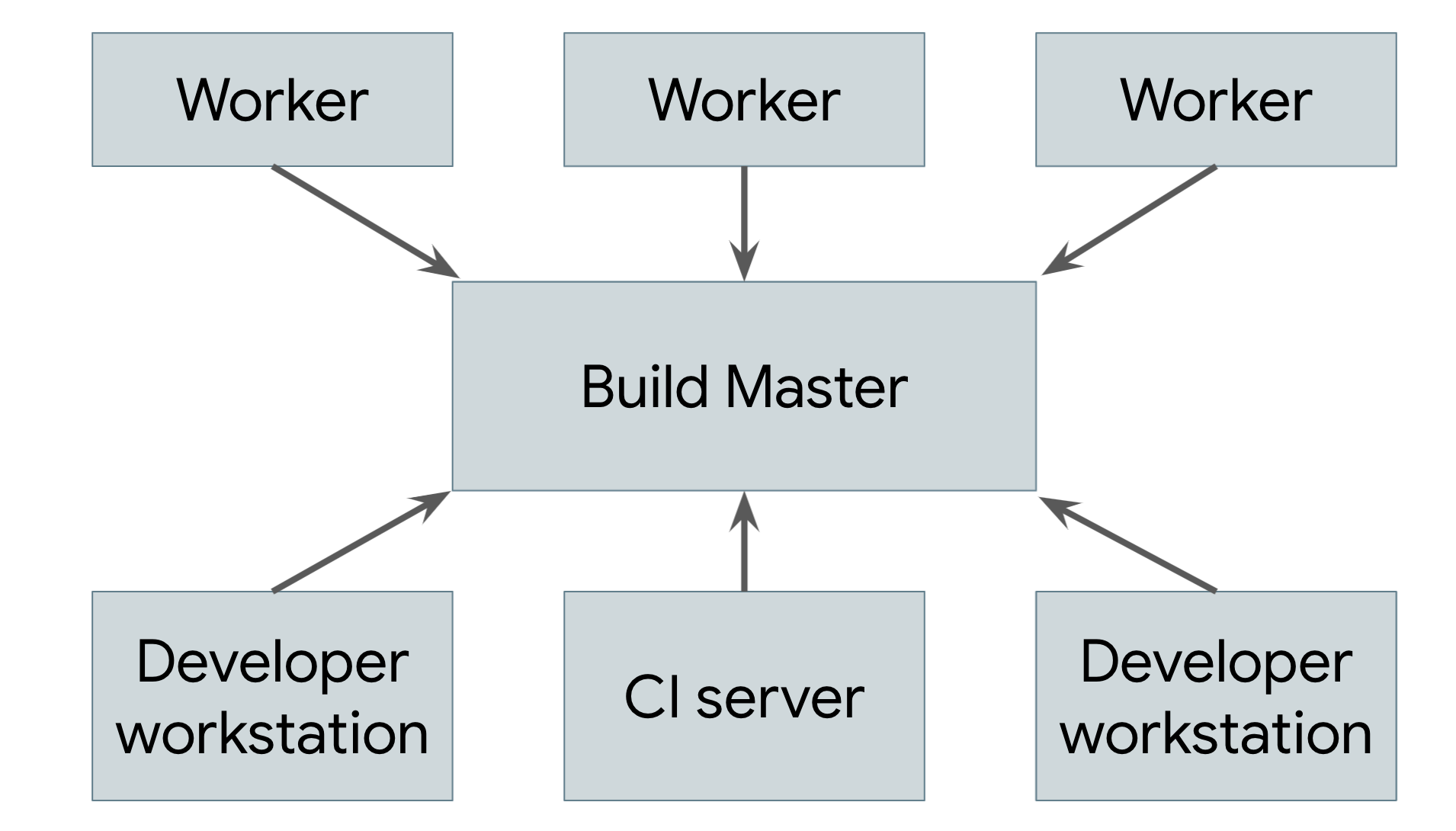

Remote caching isn’t a true distributed build. If the cache is lost or if you make a low-level change that requires everything to be rebuilt, you still need to perform the entire build locally on your machine. The true goal is to support remote execution, in which the actual work of doing the build can be spread across any number of workers. Figure 2 depicts a remote execution system.

Figure 2. A remote execution system

The build tool running on each user’s machine (where users are either human engineers or automated build systems) sends requests to a central build master. The build master breaks the requests into their component actions and schedules the execution of those actions over a scalable pool of workers. Each worker performs the actions asked of it with the inputs specified by the user and writes out the resulting artifacts. These artifacts are shared across the other machines executing actions that require them until the final output can be produced and sent to the user.

The trickiest part of implementing such a system is managing the communication between the workers, the master, and the user’s local machine. Workers might depend on intermediate artifacts produced by other workers, and the final output needs to be sent back to the user’s local machine. To do this, we can build on top of the distributed cache described previously by having each worker write its results to and read its dependencies from the cache. The master blocks workers from proceeding until everything they depend on has finished, in which case they’ll be able to read their inputs from the cache. The final product is also cached, allowing the local machine to download it. Note that we also need a separate means of exporting the local changes in the user’s source tree so that workers can apply those changes before building.

For this to work, all of the parts of the artifact-based build systems described earlier need to come together. Build environments must be completely self-describing so that we can spin up workers without human intervention. Build processes themselves must be completely self-contained because each step might be executed on a different machine. Outputs must be completely deterministic so that each worker can trust the results it receives from other workers. Such guarantees are extremely difficult for a task-based system to provide, which makes it nigh-impossible to build a reliable remote execution system on top of one.

Distributed builds at Google

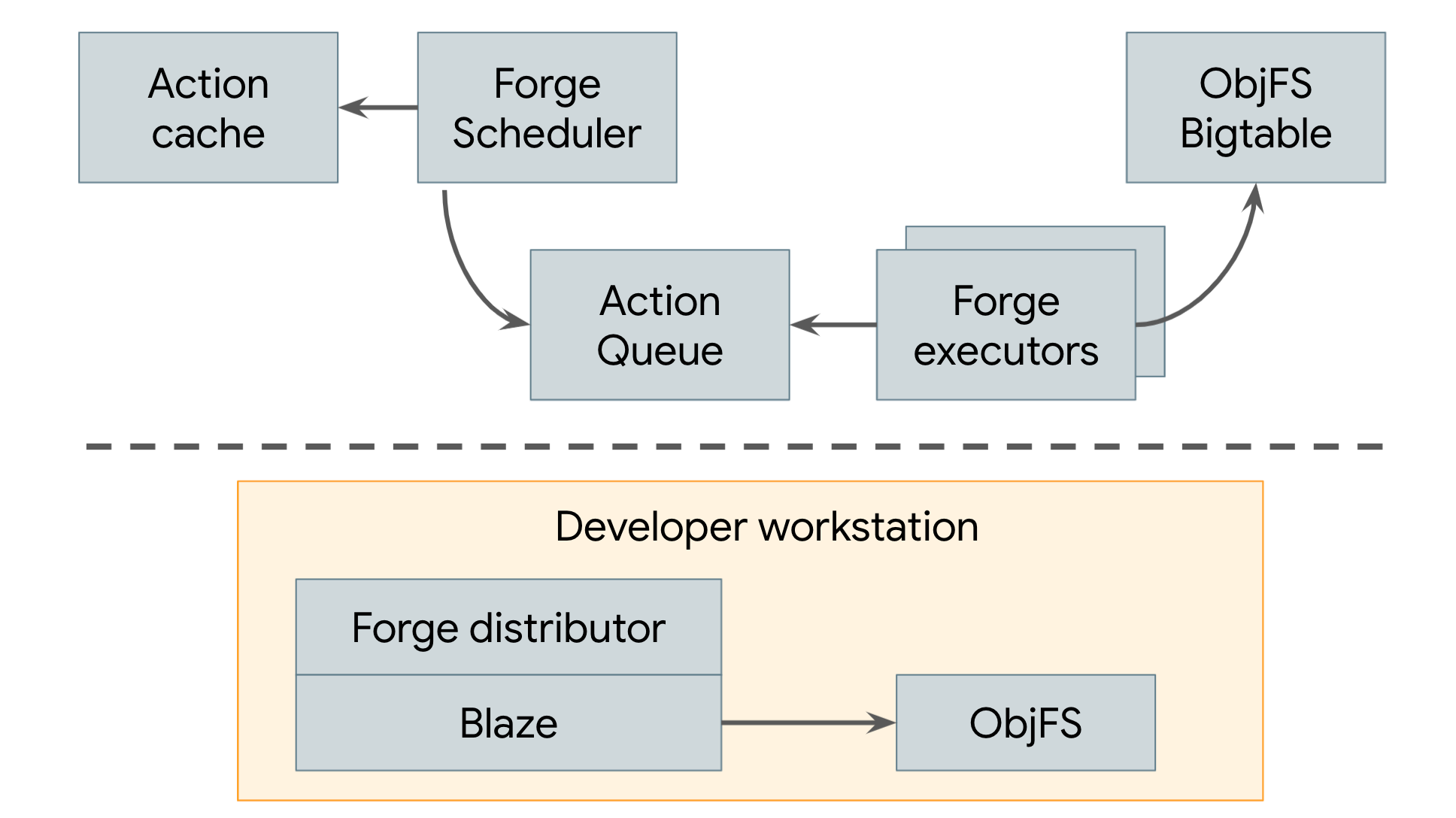

Since 2008, Google has been using a distributed build system that employs both remote caching and remote execution, which is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Google’s distributed build system

Google’s remote cache is called ObjFS. It consists of a backend that stores build outputs in Bigtables distributed throughout our fleet of production machines and a frontend FUSE daemon named objfsd that runs on each developer’s machine. The FUSE daemon allows engineers to browse build outputs as if they were normal files stored on the workstation, but with the file content downloaded on-demand only for the few files that are directly requested by the user. Serving file contents on-demand greatly reduces both network and disk usage, and the system is able to build twice as fast compared to when we stored all build output on the developer’s local disk.

Google’s remote execution system is called Forge. A Forge client in Blaze (Bazel's internal equivalent) called the Distributor sends requests for each action to a job running in our datacenters called the Scheduler. The Scheduler maintains a cache of action results, allowing it to return a response immediately if the action has already been created by any other user of the system. If not, it places the action into a queue. A large pool of Executor jobs continually read actions from this queue, execute them, and store the results directly in the ObjFS Bigtables. These results are available to the executors for future actions, or to be downloaded by the end user via objfsd.

The end result is a system that scales to efficiently support all builds performed at Google. And the scale of Google’s builds is truly massive: Google runs millions of builds executing millions of test cases and producing petabytes of build outputs from billions of lines of source code every day. Not only does such a system let our engineers build complex codebases quickly, it also allows us to implement a huge number of automated tools and systems that rely on our build.