The full specification of the Build Event Protocol can be found in its protocol buffer definition. However, it might be helpful to build up some intuition before looking at the specification.

Consider a simple Bazel workspace that consists of two empty shell scripts

foo.sh and foo_test.sh and the following BUILD file:

sh_library(

name = "foo_lib",

srcs = ["foo.sh"],

)

sh_test(

name = "foo_test",

srcs = ["foo_test.sh"],

deps = [":foo_lib"],

)

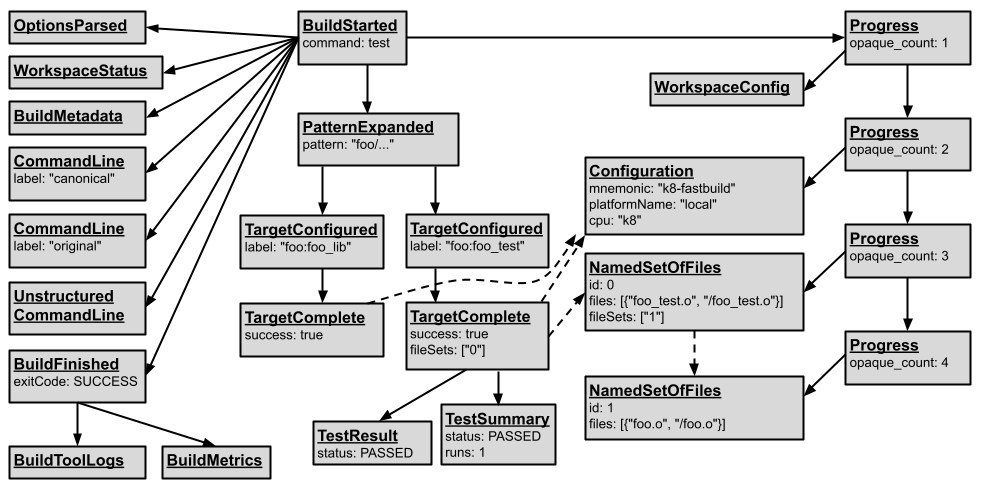

When running bazel test ... on this project the build graph of the generated

build events will resemble the graph below. The arrows indicate the

aforementioned parent and child relationship. Note that some build events and

most fields have been omitted for brevity.

Figure 1. BEP graph.

Initially, a BuildStarted event is published. The event informs us that the

build was invoked through the bazel test command and announces child events:

OptionsParsedWorkspaceStatusCommandLineUnstructuredCommandLineBuildMetadataBuildFinishedPatternExpandedProgress

The first three events provide information about how Bazel was invoked.

The PatternExpanded build event provides insight

into which specific targets the ... pattern expanded to:

//foo:foo_lib and //foo:foo_test. It does so by declaring two

TargetConfigured events as children. Note that the TargetConfigured event

declares the Configuration event as a child event, even though Configuration

has been posted before the TargetConfigured event.

Besides the parent and child relationship, events may also refer to each other

using their build event identifiers. For example, in the above graph the

TargetComplete event refers to the NamedSetOfFiles event in its fileSets

field.

Build events that refer to files don’t usually embed the file

names and paths in the event. Instead, they contain the build event identifier

of a NamedSetOfFiles event, which will then contain the actual file names and

paths. The NamedSetOfFiles event allows a set of files to be reported once and

referred to by many targets. This structure is necessary because otherwise in

some cases the Build Event Protocol output size would grow quadratically with

the number of files. A NamedSetOfFiles event may also not have all its files

embedded, but instead refer to other NamedSetOfFiles events through their

build event identifiers.

Below is an instance of the TargetComplete event for the //foo:foo_lib

target from the above graph, printed in protocol buffer’s JSON representation.

The build event identifier contains the target as an opaque string and refers to

the Configuration event using its build event identifier. The event does not

announce any child events. The payload contains information about whether the

target was built successfully, the set of output files, and the kind of target

built.

{

"id": {

"targetCompleted": {

"label": "//foo:foo_lib",

"configuration": {

"id": "544e39a7f0abdb3efdd29d675a48bc6a"

}

}

},

"completed": {

"success": true,

"outputGroup": [{

"name": "default",

"fileSets": [{

"id": "0"

}]

}],

"targetKind": "sh_library rule"

}

}

Aspect Results in BEP

Ordinary builds evaluate actions associated with (target, configuration)

pairs. When building with aspects enabled, Bazel

additionally evaluates targets associated with (target, configuration,

aspect) triples, for each target affected by a given enabled aspect.

Evaluation results for aspects are available in BEP despite the absence of

aspect-specific event types. For each (target, configuration) pair with an

applicable aspect, Bazel publishes an additional TargetConfigured and

TargetComplete event bearing the result from applying the aspect to the

target. For example, if //:foo_lib is built with

--aspects=aspects/myaspect.bzl%custom_aspect, this event would also appear in

the BEP:

{

"id": {

"targetCompleted": {

"label": "//foo:foo_lib",

"configuration": {

"id": "544e39a7f0abdb3efdd29d675a48bc6a"

},

"aspect": "aspects/myaspect.bzl%custom_aspect"

}

},

"completed": {

"success": true,

"outputGroup": [{

"name": "default",

"fileSets": [{

"id": "1"

}]

}]

}

}

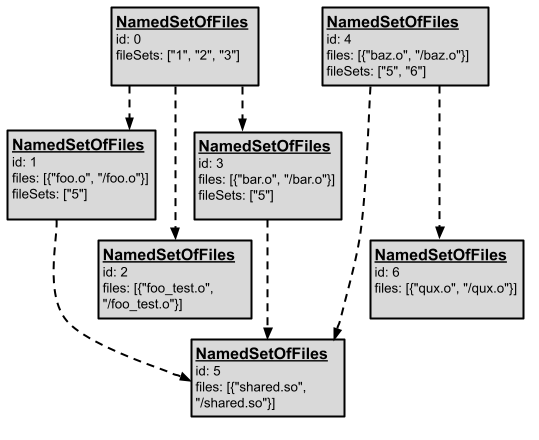

Consuming NamedSetOfFiles

Determining the artifacts produced by a given target (or aspect) is a common

BEP use-case that can be done efficiently with some preparation. This section

discusses the recursive, shared structure offered by the NamedSetOfFiles

event, which matches the structure of a Starlark Depset.

Consumers must take care to avoid quadratic algorithms when processing

NamedSetOfFiles events because large builds can contain tens of thousands of

such events, requiring hundreds of millions operations in a traversal with

quadratic complexity.

Figure 2. NamedSetOfFiles BEP graph.

A NamedSetOfFiles event always appears in the BEP stream before a

TargetComplete or NamedSetOfFiles event that references it. This is the

inverse of the "parent-child" event relationship, where all but the first event

appears after at least one event announcing it. A NamedSetOfFiles event is

announced by a Progress event with no semantics.

Given these ordering and sharing constraints, a typical consumer must buffer all

NamedSetOfFiles events until the BEP stream is exhausted. The following JSON

event stream and Python code demonstrate how to populate a map from

target/aspect to built artifacts in the "default" output group, and how to

process the outputs for a subset of built targets/aspects:

named_sets = {} # type: dict[str, NamedSetOfFiles]

outputs = {} # type: dict[str, dict[str, set[str]]]

for event in stream:

kind = event.id.WhichOneof("id")

if kind == "named_set":

named_sets[event.id.named_set.id] = event.named_set_of_files

elif kind == "target_completed":

tc = event.id.target_completed

target_id = (tc.label, tc.configuration.id, tc.aspect)

outputs[target_id] = {}

for group in event.completed.output_group:

outputs[target_id][group.name] = {fs.id for fs in group.file_sets}

for result_id in relevant_subset(outputs.keys()):

visit = outputs[result_id].get("default", [])

seen_sets = set(visit)

while visit:

set_name = visit.pop()

s = named_sets[set_name]

for f in s.files:

process_file(result_id, f)

for fs in s.file_sets:

if fs.id not in seen_sets:

visit.add(fs.id)

seen_sets.add(fs.id)